By Craig E. Litz, M.D.

Updated by Ravi Patel, M.D., May 2020

A 74-year-old female presented to her physician with a several month history of watery diarrhea and intermittent mild crampy abdominal pain. Her physical exam was normal. The colon appeared endoscopically normal except for a small incidental polyp of the sigmoid colon. Random biopsies and polypectomy were performed.

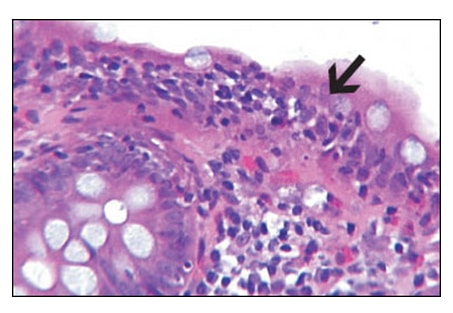

Microscopically, the random biopsies showed a marked lymphocytic exostosis (>2 lymphocytes/10

enterocytes) of the superficial and crypt epithelium with evidence of surface epithelial damage, increased

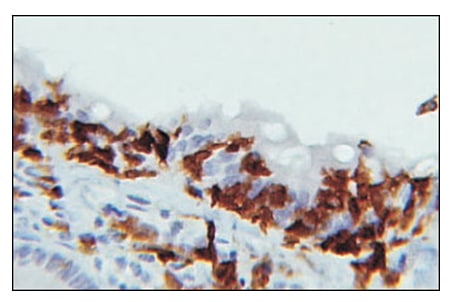

numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells of the lamina propria, intact glandular architecture, and absence of a thickened basement membrane (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2).

Immunohistochemically, the lymphocytes were T-cytotoxic cells (CD3+, CD8+; Fig. 2). The microscopic findings were diagnostic of lymphocytic colitis; an incidental hyperplastic polyp was also diagnosed.

Lymphocytic colitis (LC) together with collagenous colitis (CC) represent the “microscopic colitides” because they are defined by microscopic abnormalities alone. The two entities share several clinical and histologic features and are considered closely related. Patients are predominantly female, between 40-70 years old, and typically present with a long-standing history of watery, non-bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms frequently include colicky abdominal pain, fecal incontinence at night, and mild weight loss. Exacerbations and remissions characterize these disorders.

Lymphocytic colitis was first reported in 1989 by Lazenby, et al, after noting strikingly different microscopic features in a subset of microscopic colitides after comparing to cases of collagenous colitis and inflammatory bowel disease 3. In a recent systematic review with meta-analysis, Tong, et al, looked at 25 studies and pooled the data to have found an incidence rate of 4.85 per 100,000 person-years, female to male incidence ratio of 1.92, and 62.18 years for the median affected age 7. The incidence rate was gradually increasing up until 2000. Since then the incidence rate has stabilized.

Lymphocytic colitis was first reported in 1989 by Lazenby, et al, after noting strikingly different microscopic features in a subset of microscopic colitides after comparing to cases of collagenous colitis and inflammatory bowel disease 3. In a recent systematic review with meta-analysis, Tong, et al, looked at 25 studies and pooled the data to have found an incidence rate of 4.85 per 100,000 person-years, female to male incidence ratio of 1.92, and 62.18 years for the median affected age 7. The incidence rate was gradually increasing up until 2000. Since then the incidence rate has stabilized.

An association of the microscopic colitides with the regular ingestion of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, autoimmune diseases, and celiac disease has been proposed. Up to 45% of patients with microscopic colitis have autoimmune diseases 10. Celiac disease increases the chances of having microscopic colitis by 70-fold, and celiac sprue is highly prevalent in patients with known lymphocytic colitis (11,12). Anywhere from 10 to 35% of patients are thought to have used medication which have been associated with LC9. Several studies have cited selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and proton pump inhibitors (PPI) as drugs with strong causation for lymphocytic colitis (7,10). Other implicated drugs include ranitidine, ticlopidine, acarbose, cyclo-3-fort, flutamide, and clozapine (9).

Microscopically, lymphocytic colitis shows conspicuous T-cytotoxic mediated damage of the gut epithelium with characteristic superficial epithelial lymphocytic extravasation. Collagenous colitis is distinguished by the presence of a markedly thickened superficial basement membrane. Lymphocytic extravasation with >2 lymphocytes/10 enterocytes is generally seen in LC; however, this alone is insufficient to diagnose LC. Additional features such as increased lamina propria inflammatory cells in the upper half of the mucosa and epithelium damage must be present. Disordered glandular architecture, “bottom-heavy” lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and crypt abscesses typical of inflammatory bowel disease are not present. Occasionally acute cryptitis and neutrophilic extravasation can be seen.

LC must be distinguished from “colonic lymphocytosis.” Colonic lymphocytosis is used to describe increased lymphocytes in the colonic epithelium when there is not a true colitis (epithelium is not damaged and lamina propria appears normal). Colonic lymphocytosis is considered a common end point to many conditions and may be seen with drugs, infections of food or waterborne epidemics, resolving phase of infectious colitis, celiac, autoimmune diseases, and overlying lymphoid aggregates. Hence, LC must be distinguished from colonic lymphocytosis.

Lymphocytic colitis frequently responds to anti-inflammatory medications. Most studies and American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recommend budesonide as first line therapy. AGA suggests an initial 8-week course of budesonide to achieve remission of disease 8. Since no set quantifiable or qualifiable data such as pre- and post-treatment microscopy or endoscopy have shown reliable utility in assessing remission, clinical quality-of-life scores are used to gauge treatment effect. Relapse of disease is common (40-81%) after discontinuing budesonide and therefore low-dose continuation with budesonide is often needed (8). Other anti-inflammatories such as bismuth subsalicylate, mesalamine, or anti-TNF-alpha agents are reserved as backup when budesonide is contraindicated or fails.

References:

1. Jawhari A, Talbot IC: Microscopic, Lymphocytic and Collagenous Colitis. Histopathology 29:101-110, 1996.

2. Veress B, Lofberg R, Bergman L: Microscopic Colitis Syndrome. Gut 36:880-886, 1995.

3. Lazenby AJ, Yardley JH, Giardiello FM, et al: Lymphocytic (“Microscopic”) Colitis: A Comparative Histopathologic Study With Particular Reference to Collagenous Colitis. Hum Pathol 20:18-28, 1989.

4. Zins BJ, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ: Collagenous and Lymphocytic Colitis: Subject Review and Therapeutic Alternatives. Am J Gastroenterol 90:1394-1400, 1995.

5. Goff JS, Barnett JL, Pelke T, Appelman HD. Collagenous colitis-histopathology and clinical course. Am J Gastroenterol 92:57-60, 1997.

6. Riddell RH, Tonaka M, Mazzoleni G: Non-steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs as a Possible Cause of Collagenous Colitis: A Case-Control Study. Gut 33;683-686, 1992.

7. Tong J, Zheng Q, Zhang C, Lo R, Shen J, Ran Z. Incidence, Prevalence, and Temporal Trends of Microscopic Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:265–276.

8. Boland K, Nguyen GC. Microscopic Colitis: A Review of Collagenous and Lymphocytic Colitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2017;13(11):671–677.

9. Carmack, Susanne & Lash, Richard & Gulizia, James & Genta, Robert. (2009). Lymphocytic Disorders of the Gastrointestinal Tract A Review for the Practicing Pathologist. Adv Anat Pathol. 16. 290-306.

10.Gentile N, Yen EF. Prevalence, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management of Microscopic Colitis. Gut Liver. 2018; 12(3):227–235.

11.Green PH, Yang J, Cheng J, Lee AR, Harper JW, Bhagat G. An association between microscopic colitis and celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1210–1216.

12.Matteoni CA, Goldblum JR, Wang N, Brzezinski A, Achkar E, Soffer EE. Celiac disease is highly prevalent in lymphocytic colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:225–227.